Representation is a complex business and, especially when dealing with ‘difference’, it engages feelings, attitudes and emotions and it mobilizes fears and anxieties in the viewer, at deeper levels than we can explain in a simple, commonsense way. (Hall, 1997. p. 226)

Hall (1997) highlights many of the challenges that emerge when educators, in both formal and informal settings, seek to engage learners in the act of putting themselves in the shoes of others who, through race, nationality, gender, class, etc., appear different from ourselves (Walsh et al., 2017, p.17). This becomes even more challenging when learners' life experiences are juxtaposed with the lives of people in the past; we cannot see what they saw, experience what they experienced, or directly engage with the context of a place and a time passed. In this paper, we explore this problem through the lens of how eXtended Reality (XR), which includes Augmented Reality (AR) and Virtual Reality (VR), might enhance users and students’ engagement with historical places and historical sources as part of the process of engaging in historical inquiry. Our research specifically addresses the question: Can place-based history, that is, visits to historic sites, be structured in a way that explicitly teaches students to engage in historical inquiry to learn about the past?

Immersive technologies (experiences using XR) afford users the chance to take advantage of what is known as presence (Slater, 2009) through place and plausibility illusion (Skarbez et al., 2017). In short, place illusion is the sense of “being there,” while plausibility illusion is the feeling of being “as if real.” Designing XR experiences that take advantage of those affordances can be difficult. Much of this difficulty centers around creating opportunities for learners to engage with representations of the past - with a sense of “as if it is real” that goes beyond textbooks, films, and museum exhibits.

Over the last 14 years, our transdisciplinary team has focused on designing immersive experiences that harness the potentials of 'place illusion' and 'plausibility illusion.' This approach enables participants to experience a vivid sense of presence, which is crucial for deeply engaging with hidden and challenging historical narratives. We emphasize a disciplinary, inquiry-based approach, ensuring that these experiences are not only authentic but also experientially rich, fostering a deeper understanding of complex histories. Hidden and hard histories refer to aspects of the past that are overlooked, underrepresented, forgotten, or deliberately ignored from mainstream historical narratives, as well as histories that are considered “affectively difficult” and “conceptually difficult” because they involve traumatic, controversial, culturally sensitive, or challenging topics (Walsh et al., 2017, pp. 18-19).

These histories can be “hidden” for many reasons, including cultural suppression, censorship, or simply the marginalization of certain groups’ perspectives and experiences. Historic sites can also be hidden in plain sight or simply inaccessible due to location. “Hard” histories, on the other hand, involve topics such as race, genocide, slavery, wars, and other forms of violence and injustice that may be difficult to understand and discuss due to their complexity and ideologically charged nature. (Walsh et al., 2017). We emphasize the importance of place, the concept of “what gets processed gets learned,” and the notion that immersive experiences can provide the situational context/presence that will allow learners to have meaningful engagements with hidden and/or hard histories. A common thread running through our work stresses making visible the invisible past to encourage and support inquiry-based learning. We do this across all XR projects and exhibits by asking the guiding question, “If this place could talk, what would it tell us about the lives of the people who were here, in this place, in the past?”

In this paper, we detail the design and development of three immersive learning experiences that help learners visualize and make sense of hidden/hard histories using XR technologies, which include virtual and augmented reality experiences. These are:

By presenting these three case studies, we aim to highlight the often overlooked or neglected role of instructional design in creating and developing experiences crafted by transdisciplinary teams. These cases reveal key underpinnings and affordances of instructional design for XR-based studies of the past. When designing explorations of past events and locations using (XR), we contend that it is essential to keep the learner/user at the forefront. This is achieved by providing them with a guided historical inquiry that uses accessible/modified historical sources and explicit scaffolds to support source analysis so that the user can make evidence-based claims to close the inquiry.

In conceptualizing our pedagogical design, we integrate principles from both cognitive and constructivist theories of learning, as evidenced by scholarship in the field (Doolittle & Hicks, 2003; Hicks et al., 2012; van Hover & Hicks, 2017). Concurrently, we adopt the Understanding by Design framework articulated by Wiggins and McTighe (2005), emphasizing the importance of deliberate and thoughtful pedagogical planning to facilitate deep understanding. However, we also recognize the limited time available for learners to engage with the content within an immersive experience, whether through the time allotted to the experience as part of a field trip or in-school experience. Therefore, we leverage pedagogical strategies such as “engagement first” (Parker et al., 2013; Stoddard et al., 2022) to develop the historical narrative while learners are engaged in the inquiry, scaffolds to support and sustain the learners’ historical inquiry, and epistemic frames (Shaffer, 2006; Stoddard, 2022) that create a role or rationale for learners while engaging in the immersive experience.

At the crux of our design philosophy lies the recognition that context is not a mere backdrop but a critical element in forging a connection with historical representations. This connection is facilitated through engagement with the physical and cultural landscapes of the past and interrogation of historical artifacts, from photographs and architectural structures to everyday objects. These elements do not simply exist within history; they are tangible records and relics that bring the past to life, anchoring abstract concepts in concrete reality.

We also hold that the significance of the extent or lack of prior knowledge needs to be acknowledged. We seek to facilitate deeper and more meaningful inquiries into history by connecting new insights to learners' pre-existing understandings. Such connections empower learners to formulate evidence-based claims grounded in their own authentic experiences and interpretations. We also recognize that many learners coming to these experiences might have minimal or alternate conceptions of the past. As a result, within and through our projects, we prioritize learners’ ownership of the inquiry process.

This is achieved through an ”engagement first“ approach. This approach recognizes that participants may arrive at any immersive experience with limited knowledge of the content at hand. It is only by being within the inquiry-based immersive experience itself that they begin to work with sources to make evidence-based claims in response to the guiding question, “If this place could talk ...?” Using an “engagement first” approach emphasizes learning by doing without the need for spending time building content knowledge. That is, creating experiences framed around an inquiry that is designed to capture learner interest and curiosity to foster their immediate engagement with the historical content at hand. In short, this method prioritizes active participation over prior knowledge, allowing learners to immerse themselves directly in the XR environment and learn through doing. This experiential approach enables them to build and expand their knowledge from whatever baseline they start with, engaging deeply with the content in real-time.

Our “engagement first” approach integrates explicit strategy instruction to effectively support participants' knowledge growth with the content through an authentic, immersive inquiry. We utilize scaffolds designed to enhance participants' motivation, engagement, resilience, and knowledge development. These scaffolds are layered strategically throughout the experience, guiding participants as they navigate and interpret representations of the past. This method is a fundamental part of fostering a deep understanding of historical inquiries (Barab & Duffy, 2000; van Hover, et al., 2021). We believe that this guidance is crucial in enabling learners to adopt and apply disciplinary thinking rather than passive observation as they explore historical narratives and evidence. For example, we have included such scaffolds as “challenge cards” given to learners prior to entering the experience to help guide and signal where to pay specific attention during the experiences. These challenge cards typically guide questions that need to be answered or content that needs to be paid attention to. While XR experiences are often used individually, when working with large classes of students, different groups often get different challenge cards to work with. In this way, we can signal students to pay attention to different objects or content, then come back together at the close to summarize key or unique insights that are built into what is often a complex environment.

We also make use of a historical thinking scaffold/protocol called SCIM-C (see Figure 1) for learners to use as they analyze a range of short and accessible historical sources (documents, photographs, oral histories, maps, etc.) to make evidence-based claims (Hicks et al., 2004; Hicks & Doolittle, 2008; van Hover, et al., 2021). The scaffold/protocol is designed to let learners quickly Summarize and Contextualize a source before making Inferences about the source and then Monitor their own thinking and understanding of the source. Finally, the protocol encourages students to Corroborate and compare within and across sources to develop evidence-based accounts to answer the guiding question, “If this place could talk, ...”

Figure 1

SCIM-C

.jpg)

Note. A protocol for analyzing historical sources

Additionally, we often employ epistemic frames as scaffolds to engage learners, help guide their activity, and sustain their interest. These frames encourage learners/visitors to take on roles within the experience, such as junior detectives who are tasked with finding out what life was like for people on a derelict historic site or time travelers who are tasked with stepping back in time and walking in the footsteps of others as they explore the guiding question. The intent is to create authenticity in the experience to facilitate the process of inquiry and action, to build and elaborate on learners’ prior knowledge, and to foster creative and intellectual thinking.

Moreover, when possible, we build in feedback opportunities that are designed to serve as a navigational beacon for learners, orienting their attention and sustaining their analytical endeavors. Feedback is not used as a corrective tool for scoring responses but rather as integral to maintaining engagement with the historical sources and analysis that constitute successful inquiry. For example, in CI Spy, learners had to locate, analyze, and rate sources using the SCIM-C protocol prior to moving to the next area (and related sources) of the historic site, with the true nature of the site only revealed when the entire site and each of the sources had been explored and analyzed. In the Vauquois Experience, photos are used to visually block the learner’s path, encouraging them to slow down and attend to the visual, spatial, and textual (audio narration) information provided at certain locations before continuing through the experience.

The processing of historical information is not a one-off event but a recurrent endeavor. Multiple engagements with historical sources are essential to allow learners to corroborate evidence, strengthen their conceptual connections, and cultivate structured evidentiary claims. This iterative process is vital for deepening understanding and constructing knowledge. To that end, for each location or point of interest, multiple sources are curated, often encompassing different media types, and offered to the learner to spend time on and corroborate. In CI Spy, for example, at one location, a simulated classroom viewed through the window of the primary historic building on the site presents images of student schedules, former students’ notes from French class, (with transcription), audio interviews with former students, and 3D models of classroom materials for analysis and corroboration.

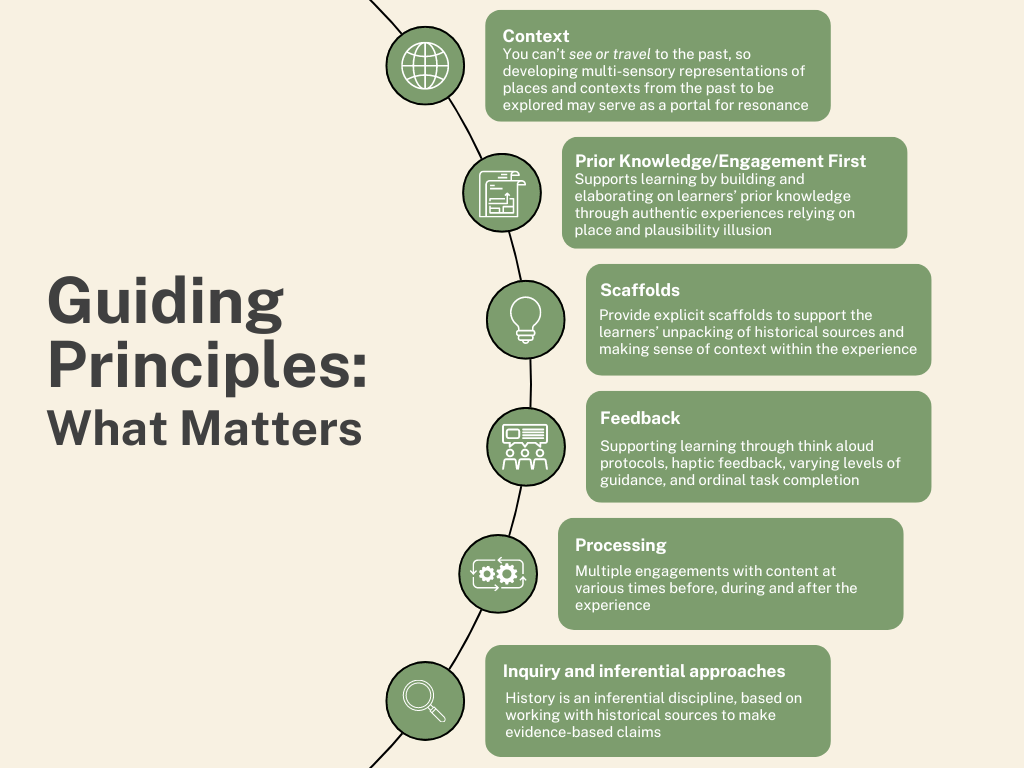

Finally, as a whole (see Figure 2), our guiding principles emphasize that the study of history transcends the passive reception of narratives. We endorse an inquiry-based approach that foregrounds the importance of inferential thinking. Engaging with pivotal questions and historical sources is paramount in constructing evidence-based claims. Through this approach, learners come to appreciate that history is not merely a sequence of events to be memorized but a dynamic discipline that requires active interpretation and understanding.

Figure 2

Our Guiding Principles

Note. Our principles are based on cognitive and constructivist learning theory

Our pedagogical design is meant to leverage what XR can offer in terms of visualization, engagement, and learning by doing. Our exploration of what XR offers for history education is described in the following section.

Our exploration into the potential of extended reality (XR) within historical education has been undergirded by a recognition that presence, or 'place illusion,' and 'plausibility illusion' are central to understanding how XR can deeply engage learners and create deeply immersive environments where learners can virtually experience and interact with representations of past places, events and individuals. Other research into the experience of and interaction with the past through XR shares common themes around engagement, interaction with the material and one another, and historical empathy. In a case study of an AR experience designed for children exploring a Spanish Civil War bomb shelter exhibit, Schaper et al., (2018) found that the augmentation of the exhibit fostered interaction in the form of direct pointing and commenting on the part of the learners. Any displayed material was best paired with an immediate activity or was perceived by the learners as a passive experience. Liao and Humphrey’s (2014) research illuminated the potential of the AR tool Layer to create content to communicate about public and private spaces, to help visitors think more deeply about and make sense of places and spaces, and to help historicize and memorialize public places and space. Graham, Zook, and Boulton’s (2013) examination of how AR can (re)present and (re)work our understandings of urban spaces, and places illustrate that the creation of spatialized information and the emerging technologies used to code space and mediate our understandings of these spaces are neither neutral nor static. In considering how immersive experiences can be received by users, Rouse et al., (2015) introduced the MRx Framework, which emphasized Mixed Reality’s role in expanding educational environments in terms of how users can interact within and through places and spaces through the esthetic, performative, and social dimensions as individuals or groups.

A great deal of work has been done regarding what XR affords for the acquisition of new skills, interaction with places/spaces and contexts, and engagement with perspectives of other people over time and space that are otherwise inaccessible (Fitzpatrick et al., 2021). XR technologies have been used to create virtual field trips to provide students with a realistic representation of the place and historical context and to support inquiry-based learning experiences across time within a space (Johnson et al., 2017). In a study of location-based AR designed to supplement a historical site visit, Efstathiou et al. (2018) found a statistically significant increase in both historical empathy and conceptual understanding in a pre-and post-test design when compared to a field trip to the same site without the accompanying AR supplement. Recent efforts to incorporate XR to capture Holocaust witness testimony and to virtually transport users to Holocaust concentration camps, while touted as an important way to walk in the footsteps of others while teaching complex and sensitive historical subjects, also highlight the need for a delicate balance between technological opportunities for fostering empathy and enhancing student learning with the risks of diminishing the lived traumatic experiences of “others” in the past (Marcus et al., 2022).

With these factors in mind, there are numerous challenges to the application and integration of XR into teaching, including the nature of the discipline or subject matter, classroom contexts/conditions, and the curriculum itself. In this section, we describe our approaches to these challenges based on over a decade of experience designing immersive experiences for history education.

History cannot be observed directly. However, we contend that XR can represent the past to support historical inquiry and the development of historical empathy while engaging additional senses and leveraging place and plausibility illusion (Skarbez et al., 2017; Sweeney et al., 2018). In the study of history, understanding context is crucial. Equally important is the concept of 'place' — the actual locations and spaces where historical events unfolded provide a tangible connection to the past for learners. Many stories of national significance connect to local places and their histories. Those local sites may not have the treatment of, say, the Gettysburg Battlefield or Jamestown, with stories and residue of the past hidden in plain sight amongst derelict buildings and unmanaged landscapes.

Techniques like redirected walking (Yu et al., 2018), which allows users to walk in a physically limited space while experiencing the illusion of unrestricted movement, can contribute to both illusions. On the other hand, technical glitches, such as interruptions in the VR experience or visual inconsistencies, can disrupt the user’s immersion. When the virtual and physical experiences fail to align, it can pull learners/users out of the necessary level of coherence to maintain either illusion.

This disruption undermines the effectiveness of immersive learning experiences by breaking the engagement and forcing the user to suspend their willingness to believe that the experience is “as if real” and recognize the artificiality of the environment and experience. The achievement and maintenance of place and plausibility illusion are in the service of supporting realistic behavior on the part of the learner (Slater, 2009), whether that is in the collection and analysis of evidence via an explicit scaffold for young learners or through encouraging curiosity and investigation for adults.

We have worked with learners ranging from ten years old to senior citizens. The epistemic stance of being a “history detective” (see section on Christiansburg Institute) that we have used when working with young learners is clearly inadequate for a set of adult learners. However, asking those adults to imagine walking in the footsteps of others while touring a historic site (see section on Solitude) functions similarly to our approach with youngsters. Both leverage the “engagement first” strategy to reinforce or support the place and plausibility illusion discussed above.

History is an inferential and inquiry-based discipline. Using structured inquiries can drive understanding (van Hover et al., 2021; Fitzpatrick et al., 2021). An “engagement first” design can support learners in sustaining a high level of effort over an extended inquiry. Tailoring a learning experience to go beyond show and tell or information collection as in a scavenger hunt, is not only possible but critical to the success of any immersive experience intended to support history learning.

There are numerous challenges to the application and integration of XR into teaching; many are practical in nature, such as access to equipment, software, and experiences appropriate for the classroom, and classroom management, to name a few. Some of these obstacles can be surmounted through designing learning stations, where an immersive experience is one station amongst several that are intended to get students actively engaged with materials. Some of these challenges can be overcome by designing learning stations — dedicated areas within a classroom space — where students rotate through multiple interactive activities, including immersive experiences. Each station focuses on engaging students actively with specific educational materials, thus diversifying and enriching their learning journey. Helping teachers evaluate immersive experiences for suitability in their curriculum can go a long way toward improving the usability of XR in the classroom, computer lab, or field trip (Fitzpatrick et al., 2021).

We contend that properly designed instruction must be user/learner centered. Custom-designed immersive experiences require transdisciplinary teams to build learning content married to meaningful objectives and assessment, just like any instructional design task, but with specialists in art, development, sound, and graphics.

Understanding the technical and artistic approaches required to develop quality immersive experiences as well as leading the instructional design process puts a great deal of responsibility on the designer. This can sometimes lead to tension between the subject matter expert (SME) and the designer as to not only what the expected experience outcomes are but also what the pedagogical approach will be. If the SME’s conception of the immersive experience is limited to show and tell or demonstration, with no instructional strategy linking activity to assessment, the resulting product, we argue, is the antithesis of “learner-centered design.” Walking the SME through the instructional design process can act as an opportunity to demonstrate how the affordances of immersive experiences can support learning activities that support their goals for their students.

The following three case studies describe how our team has designed immersive learning experiences that help learners visualize and make sense of hidden/hard histories through XR technologies. The need to discuss the affordances of the XR technology in each case is especially salient when you consider that some of the experiences described are in situ on an actual historic site while others are not (AR versus VR). Of the three cases, two were augmented reality, while one was multi-part, but all were VR. From a technical standpoint, each of the cases share some commonalities and some key differences. Each of the projects was developed in the Unity™ game engine, though the final deployments ranged from iOS™ on iPads™ (CI Spy), to Android™ based wearable AR in a Google Mirage™ headset (Solitude), and Steam VR™ or Faro Scene VR View™ (Vauquois). Later development on Vauquois focused on an accessible version developed in Blender™ and Mozilla Hubs™ that was used on Chromebooks™ and Oculus Quest™ headsets. In the cases of the AR projects, CI Spy began in the Metaio™ SDK, which later became Apple ARKit™. For Solitude, and Apple ARKit™ version was built for iPads™, and a Google ARCore™ version was built for deployment on the Mirage™ headset. Other tools employed across our projects included Autodesk Maya™ for 3D modeling and Adobe Photoshop™ for image editing.

CI Spy is a mobile AR app designed to support fifth-grade students in investigating a hidden local history through the derelict historic site of a former African American school, the Christiansburg Institute (CI). CI served the African American community of Southwest Virginia from 1866 until 1966. At its peak, the school had 13 academic buildings, and Booker T. Washington once served on its board of supervisors. After the school closed in 1966, its holdings were parceled off to developers and later destroyed. All that remains of the once 185-acre campus is the Edgar A. Long Building (Image 1), currently inaccessible and in a dilapidated state, on a 3-acre lot. Given the state of CI and the “missing campus”, students took the role of junior history detectives to solve a historical mystery, hence CI Spy.

Image 1

The Edgar A. Long Building

Note. Area teachers try the AR view into the Edgar A. Long building

In this project, students explored the site using mobile AR (tablets) with historic sources located at important locations around the site, using an explicit scaffold to make evidence-based claims about this historic school. While the field trip was part of a larger unit introducing historical inquiry through the lens of civil rights, the CI Spy experience was designed to be a standalone activity, focusing on a hidden local history. The children had 40 minutes on site for a tightly focused and guided field inquiry. The less the students knew about CI prior to the field trip, the better, as “engagement first” served as the epistemological frame for inquiry.

Applying the Understanding by Design framework (McTighe & Wiggins, 2012) to the design of this experience, we sought to directly observe the young learners’ ability to “explain, interpret, apply, shift perspective, empathize, and self-assess” (p.1) as part of an historical inquiry. To help our young learners to sustain an inquiry using XR, we developed a guiding question: If this place could talk, what would it tell us about the lived experiences of the people who were once here? To answer that question, the students were tasked with developing a junior-detective report using the evidence they had collected on site. SCIM-C was used to help them analyze the sources embedded throughout the site, in its one real building and several virtual buildings.

Once on site, students see computer-generated information layered onto the real world through their tablets (AR) and can enter virtual buildings and explore them in a non-immersive VR mode. The students utilized the app’s time slider feature to see true-to-scale 3D models of CI’s buildings in their original locations. CI Spy allowed students to “visit” three of CI’s buildings, which through XR were made accessible (Image 2). The three lost buildings included the Long Building (academic building), the Scattergood Gym (extracurricular focus), and the Trades Building (trade/skill preparation).

Image 2

Students Using CI Spy to Explore Evidence

Note. Students view an extant building in AR mode, then enter it in VR mode to interrogate evidence

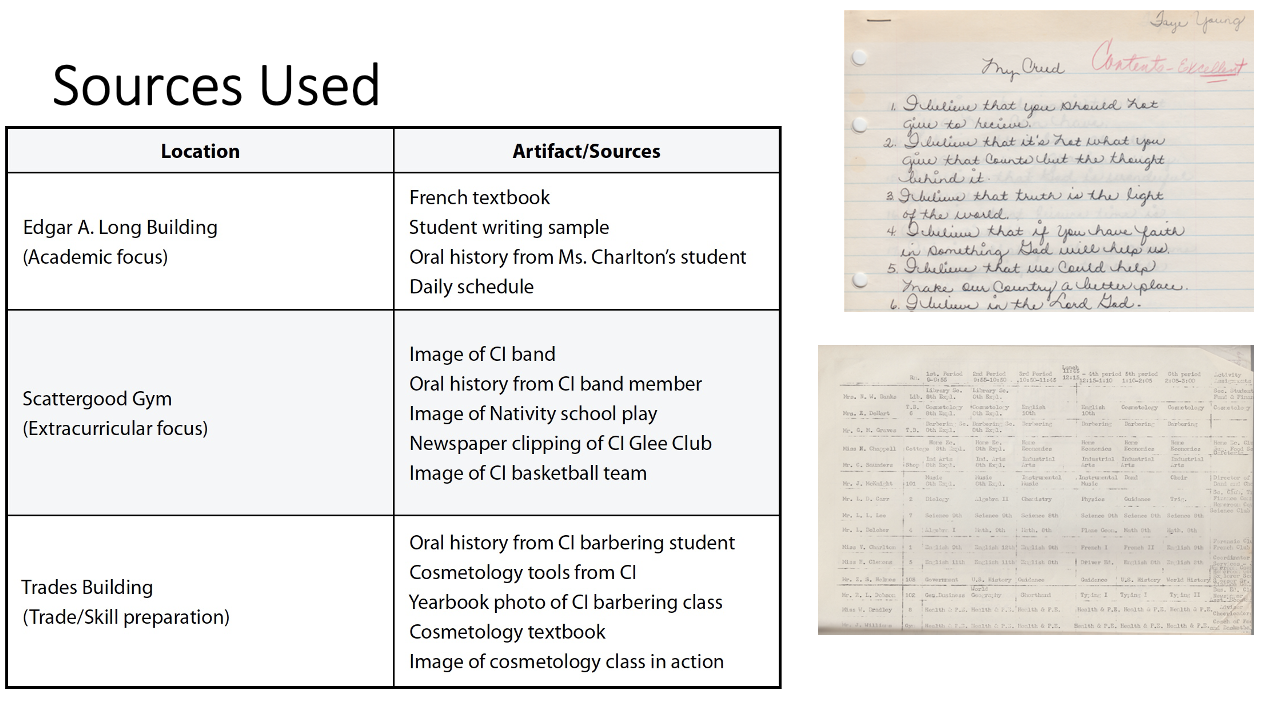

Housed within these buildings were artifacts including oral histories, student work samples, school documents, textbooks, and photographs that students analyzed on site using SCIM-C. Special attention was made in the design of CI Spy to include sources representative of a range of student reading abilities and included visual images and brief text documents along with more complex, extensive text documents (Figure 3).

Figure 3

Sites and Sources at Christiansburg Institute

Note. The real and virtual buildings were matched with specific sources.

Their analyses were saved and stored within the app — after completing each individual source analysis using the SCIM-C scaffold within each building, the app prompted students to save their work. The research team referred to this storage within the app as a "virtual backpack." In addition to the SCIM-C scaffold, students were asked to rate each piece of sources using a three-star rating system that awarded stars based on student perceptions of its significance in relation to helping answer the guiding question. Upon returning to the classroom for the final two days of the instructional unit, information from students' virtual backpacks including sources collected, their on-site analyses, and star ratings were made available to help in the drafting of their final written reports.

Designing a historical inquiry for fifth graders at an unmanaged historic location using XR created several challenges, primarily around the selection and presentation of sources, pacing of the learners’ activity while on site, managing what was an initially envisioned as an open-ended inquiry, and storing the product of the students’ field analysis for later use in building their historical accounts. Our decisions regarding the placement of sources were informed both by context and geography. For example, interviews, images, and models of trades-related activities were placed in the virtual Trades Building for context and to move the students to a variety of physical locations on the abandoned campus. Had we made it possible to “enter” the Trades Building from a distance, students would have done so while staying in one spot and looking around them.

Our initial open-ended inquiry did not survive initial pilot testing. The children enjoyed viewing the extant structures provided in AR and moved throughout the site at their own pace. However, they would often treat locations at stops in a scavenger hunt and did not spend time analyzing the sources using the SCIM-C protocol. To provide pacing to the inquiry, students could not ‘unlock’ certain locations until they had entered notes and a rating for each piece of evidence located at the points of interest they had already visited. This evolved into our final student management strategy informed by guided discovery (Clark et al., 2012), where we scripted an exploration of the site but left students to spend the time they felt was best at each, albeit through the pacing method mentioned above.

With the primary analysis occurring on-site, a method of storing students’ collected evidence, ratings, and analysis for later retrieval had to be developed. This was accomplished through a database, with the contents of each groups’ analysis being exported and printed off for each participating teacher to work with their students in preparation for the students’ evidence-based historical account of Christiansburg Institute.

The augmented reality project at the historic Solitude site was designed to explore the application of wearable augmented reality in an outdoor environment. Solitude, the oldest structure at Virginia Tech, holds a largely unrecognized historical significance among its community. In celebration of the university's 150th founding anniversary, we created an immersive experience to chronicle Solitude's past, from its beginnings on indigenous lands to its operation as a nineteenth-century slave plantation up to the present. The project intended to highlight the marginalized and forgotten narratives that are pivotal to the full historical tapestry of the university. Designed for an adult audience in an informal learning context, the experience utilizes an open exploration of the environment, resulting in different learner experiences. Instructional design

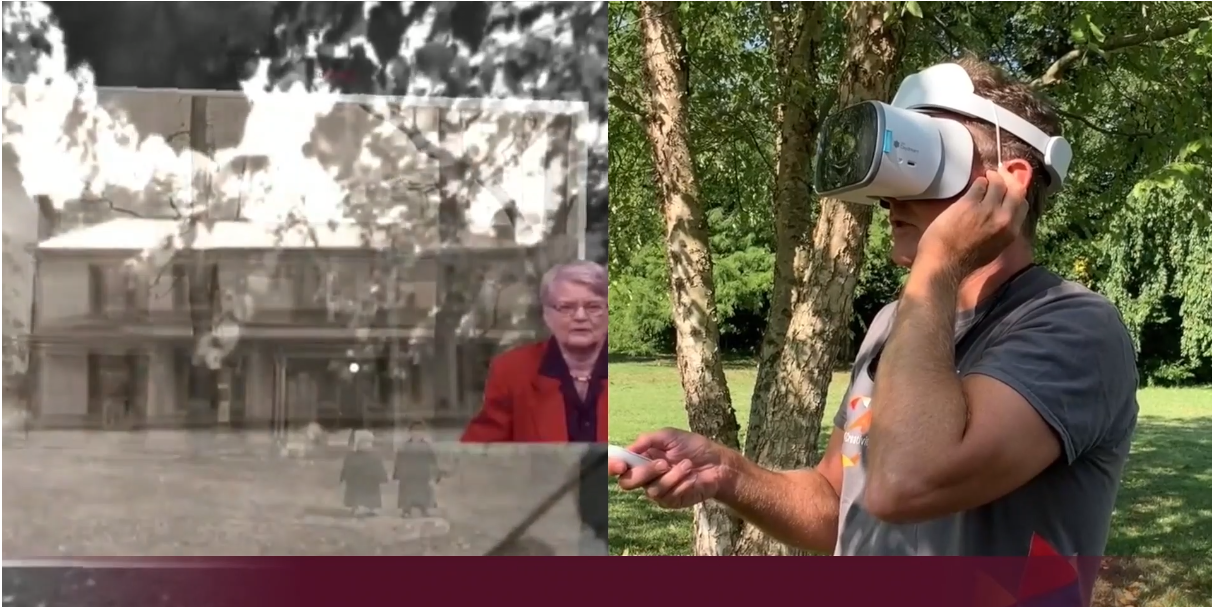

Exploring Solitude was primarily an outdoor augmented reality project (Image 3), though there were accompanying displays and a projection mapping exhibit inside the building itself.

Image 3

Wearable AR at the Solitude Historic Site

Note. The user’s view (left) while wearing the AR headset (right) on the site.

The outdoor AR experience was designed for an adult audience with minimal guidance. That guidance was provided via our guiding question of, “If this place could talk, what would tell you about the people who were once here?” We built verbal and visual signaling into the experience to provide visitors with suggestions on where on the grounds to position themselves to explore the site but did not dictate the order or time spent at each of the key points of interest.

This was a place-based experience, where the evidence and accounts were connected to the grounds and structures on the site. The historic sources were carefully chosen to allow for deeper exploration by visitors and included documents, images, 3D models, and video interviews with living ancestors of the enslaved. A descendant of the enslaved family provided a narrative account of how their family remembers the events of the past alongside records of those same events. Our instructional design had to consider not only the number and quality of the sources but also questions related to the instructional content and experience design, including how can visitors interact with sources, for how long, and where on the grounds should the sources be placed? One key decision was to initially provide visitors with a limited number of sources to support their claim-making, but additional sources were made available as an option given participants’ interest and time.

From an information presentation perspective, decisions had to be made about how best to display our mainly document-based sources for not only readability but also context. The site is much more confined than Christiansburg Institute, for example, but has multiple structures that were leveraged to provide physical context to the sources. Several designs were tested, with early designs attempting to ground the documents and maps on virtual tables or stands, but we settled on a free-floating presentation of the sources at eye-level to be selectable by the user (Image 4), allowing them to focus on what they wanted to explore (Gutkowski et al., 2021).

Image 4

AR View of Documents at the Site

Note. The final presentation of historical documents in the Solitude AR project.

In the end, while the project began as a wearable AR experiment, for usability purposes, we chose to push the app to mobile AR (Apple ARKit™ on iPads™) for use by the public.

While the preceding cases were based on local history, the Vauquois Experience was designed to make the inaccessible tunnels of a First World War site in rural France (part of the Western Front) and the hidden histories of the French and German soldiers there accessible to schoolchildren and the public in the United States. What makes the four years of fighting from 1914 to 1918 at Vauquois unique is that this hilltop village became the site of extensive and ongoing tunnel warfare. Because of its geography, Vauquois was an important strategic location for the French and Germans. One of the few high points in a valley region known as the Meuse-Argonne, the hill of Vauquois was a key position to observe Verdun and monitor transportation routes in the area. As a result, neither army was willing to relinquish control of the hill despite its dwindling strategic significance as the war came to an end.

This interactive exhibit offers visitors a series of connected independent experiences that together allow them to explore and investigate the compelling question: if this place could talk, what would it tell us about the nature and impact of World War I on the people, places, and environment on the Western Front in France between 1914-1918? These include a room-scale VR experience, a VR experience that includes passive haptics (Image 5), an online VR experience in Mozilla Hubs, laser scanning data exploration in VR, and interactive maps using 360-degree video. One or more of these products have been installed at a local Middle School, multiple university libraries, online, and in multiple museums, including the Smithsonian’s National Museum of American History. Thousands of visitors to the National Museum of American History explored the physical exhibit over the course of three days at the ACCelerate Festival. The design for this experience within museum settings had to account for visitor queuing, what we could teach them about the context while in the queue, and throughput, which limited time per visitor, while the design for the Middle School installation had a different set of requirements, leading us to work with the teachers to weave the VR experience into a set of learning stations.

Image 5

The Vauquois Experience

Note. A student explores the Vauquois experience which blends the virtual and physical in one exhibit.

The primary challenge we encountered in our design was how to give learners/visitors the ability to walk naturally (as opposed to use controllers to navigate) through the physical and virtual tunnels in a limited space while learning about the history of Vauquois and the experiences of both French and German soldiers. Our solution to the space problem was to employ a technique called redirected walking (Yu et al., 2018). Redirected walking comes in many forms, and is typically used in large-scale VR experiences; the form we chose was a rotation of the virtual world around the user’s head while they looked around in each corner of the virtual tunnel (see a video demonstration at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=wISSavmDYKs).

Learners of various ages approached the experience in different ways, but the majority chose to race through it in their excitement or walk quickly as if it were a test to get through. Thus, we had to control the pacing. After iterative design and testing, we chose to use period photographs coupled with audio narrative to guide visitors’ attention and pacing, both in the redirected walk segments and at key points of interest. These photographs would virtually block the tunnel until the narrative commentary or audio had been completed. Once completed, the images faded out so the user could continue to explore until the next point of interest.

As learners/visitors move through the exhibit, they encounter different spaces, including living quarters with artifacts and photos or images from the period. Users hear the story of Vauquois through their VR headset. Not only are visitors able to walk through the virtual environment, but they can also interact with physical representations of objects that are based on actual artifacts and material culture left behind 100 years ago. For example, visitors can reach out and touch a carving within the tunnel and pick up and carry a lantern as they move through the virtual reality tunnel itself.

The instructional goals for the experience included gaining an understanding of what life was like for people there, the futility of war, the scale of war, and the technology used, again using our guiding question: “If this place could talk, what would it tell us about the lives and experiences of the French and German soldiers engaged in tunnel warfare for four years a century ago?” In terms of their epistemic stance, they take on the role of archaeologists, exploring the tunnels and the sources and material objects left behind. This decision grew from the research team’s experience working at the site with rescue archaeologists and a desire to model their decision-making processes. We sought to achieve this understanding through having the students walk in the footsteps of others. The exhibit leverages the physical structure that matches the shape and scale of what is seen in VR while the students/visitors walk through the site carrying a lantern as a light source.

In both the public museum and school activity versions of the Vauquois VR experience, learners are issued challenge cards (Figure 4) to guide their attention throughout. Both main versions made use of “learning stations” where visitors were offered a seated VR exploration of our raw laser scanning data, offering insight into the scale and form of the vast tunnel network at the site, in addition to the multi-sensory haptic experience of the tunnel.

Figure 4

Example Vauquois Challenge Card

.png)

Note. Challenge cards were distributed to prime learners’ attention prior to the experience.

Working in collaboration with middle school teachers, we developed this series of learning stations in addition to the haptic experience and laser scanning data that were rolled into a field trip experience. The field trip was part of, and an enhancement of, the existing curriculum on the First World War. The exploration began with setting the context and providing the overall guiding question with the supporting challenge cards. In addition to the previously described stations, the students engaged in a map activity with 360-degree video attached, giving them a view of what the site looks like today. The field trip concluded with a group discussion led by the teacher.

Our work in XR, or immersive experiences, and history has generated key considerations when designing history instruction with XR. First is the importance of visualization and how it can make seen the unseen. Drawing attention to features of real historic places, providing evidence or sources that are not otherwise provided in situ, or providing access to times and places without temporal or geographic constraints. Leveraging XR’s ability to provide place and plausibility illusion can support learner engagement, interaction with the sources (including the place itself), and the overall effectiveness of the XR experience as it relates to the learning goals.

Practical considerations include acknowledging the significant amount of time that activities using immersive experiences involve and strategies for fitting those activities into a crowded curriculum (group versus single-user experiences, setup time, and out-of-classroom time). When custom building an experience, there is the potential for tension with the subject matter expert or, conversely, the opportunity to help them understand the backward design of instruction. Additionally, accessibility and sustainability are important factors. XR experiences are visually dominant ones, and though work is being done to improve usability for a range of users, there are physical and preference-based constraints on people’s ability or willingness to wear a VR headset, for example. Related to that point, visually immersive (head-worn) VR is typically a single-user experience. This has obvious impacts on its utility in group and/or collaborative learning experiences from a pedagogical perspective, but also from a classroom management perspective. As previously described, we combat this by making XR one of several learning stations within a unit of instruction. Sustainability is difficult from both a creator's standpoint and a consumer's standpoint. Technology changes rapidly and constantly; keeping a custom-built experience functional for schools, museums, etc., after the conclusion of the performance period of a grant is a serious challenge. Likewise, for teachers, finding and being able to continue using applications, even award-winning teachers, is challenging as the platforms and devices change and the original developers move on.

Pedagogically, we feel it is critical to maintain attention on the principles of learning you choose to employ (for example, we know we must provide sources and a scaffold for interrogating those sources), controlling pacing, and how much guidance you provide. With a well-planned inquiry, sustaining that inquiry is important. XR for history education does not function without well planned pedagogy, but with that planning and support in place, it can:

There are ethical considerations, particularly when attempting to evoke historical empathy or perspective-taking, as there can be inherent biases in the creators of the story or experience, as there can be with other historical representations. Additionally, assessment is a hard problem to solve, with the bulk of analysis focusing on dimensions such as satisfaction, usability, and engagement. Integrating assessment into the experience in a contextually relevant way is a key challenge and opportunity for designers.

As we design instruction for different historic contexts that rely on different technical approaches, we recognize that these experiences benefit from being inquiry-based, focused, with a managed pace and clear signaling of what users/learners need to pay attention to and process in order to answer the guiding question. With the Christiansburg Institute project, learners couldn’t access certain sources until they had completed an analysis of the preceding sources. We recognized the epistemic stance and “engagement first” as a principle to motivate and sustain the inquiry. With Vauquois, we controlled the pace with challenge cards and signaling images that discouraged moving through the exhibit without attending to the narration and visual sources provided. With the Solitude project, we suggested where visitors should look for sources and where on the grounds those sources were placed, such that they moved to places on the site we determined were important, though they could choose to gain framing knowledge first or dive right into the AR exploration.

In summary, a consistent element of our design process is bringing the person engaging with the instruction front and center and providing the user with an inquiry-based scaffold, and accessible and varied sources. Though all of our guiding principles can’t be used at the same time on every project, we have applied the relevant guiding principles along with very specific scaffolds and strategies for young learners to process sources and for adults to know what to attend to engaging in a place-based historic inquiry around hidden or hard histories.

The authors would like to thank Sarah Tucker for her assistance in designing the figure on our guiding principles.

The authors would like to thank the National Science Foundation for their support of our Christiansburg Institute project under grant number IIS-1318977.