Postsecondary institutions serve a diverse range of students with varying needs and challenges. There is a growing challenge for faculty to provide support for increasingly diverse student bodies on college and university campuses (Bastedo et al., 2013; Hromalik et al., 2020). Implementing inclusive pedagogy through UDL can reduce learning barriers for diverse students (Basham & Blackorby, 2021). Inclusive pedagogy can be defined as “making learning materials and teaching methods accessible to as many students as possible by considering a range of diverse student identities, including race, gender, sexuality, and abilities and centering these diverse identities in developing educational practices” (Association of College & Research Libraries, 2022). There is a need for UDL to provide inclusive pedagogy (Carlson & Dobson, 2020; Lowenthal et al., 2020; Redstone & Luo, 2024). UDL can reduce the need for students to disclose their diagnosis for accommodations, which would reduce demands on student support services and become more neurodiversity-inclusive universities (Hamilton & Petty, 2023). UDL can improve student persistence and retention (Espada-Chavarria et al., 2023; Garrad & Nolan, 2023; Olivier & Potvin, 2021) through providing flexibility and alternative ways for students to interact with each other and faculty and demonstrate what they’ve learned (Rogers-Shaw et al., 2018). UDL creates more chances for academic achievement and promotes the design of inclusive learning environments that meet the needs of a diverse student population (Rogers-Shaw et al., 2018).

It can be challenging to apply UDL, particularly in higher education where faculty are often not required to master pedagogical knowledge in order to teach (Hromalik et al., 2020). UDL is a complex framework with 31 different checkpoints under nine different guidelines and three overarching principles (CAST, 2018), making it challenging for instructional designers (IDs) and faculty to choose how to implement the framework (Stefaniak et al., 2024). This research addressed this challenge from a hermeneutic phenomenological perspective to provide a rich understanding of the lived experience of faculty and IDs in UDL implementation in higher education. The theoretical framework for the study was hermeneutic phenomenology. Phenomenological research has the primary goal of reaching an understanding of the meaning of phenomena (Vagle, 2018). Hermeneutic phenomenology is the study of experience and meanings (Friesen et al., 2012). Hermeneutic phenomenology is well suited to explore teachers’ understanding about pedagogical strategies (Boadu, 2021), such as implementing UDL.

The purpose of this hermeneutic phenomenological study is to explore the lived experience of implementing UDL in higher education and the meaning that faculty and IDs ascribe to this experience. Findings can be used to improve UDL training and implementation efforts of faculty and IDs. There have been very few phenomenological studies regarding UDL implementation in higher education (Black et al., 2015; Fovet, 2020 & 2021; Takemae et al., 2018) and none focus on faculty and ID lived experiences or the meaning they hold for UDL implementation. The overarching research question for this study is: what is the meaning that faculty and IDs ascribe to the experience of implementing UDL in higher education? The research sub-questions include:

What are the lived experiences of faculty and IDs when implementing UDL in higher education?

What meaning do faculty and IDs that have implemented UDL in higher education ascribe to UDL?

What process do faculty and IDs use when planning to implement UDL in higher education?

Universal design for learning (UDL) is a framework that includes multiple means of engagement, representation, and expression of learning. According to the Center for Applied Special Technology (CAST), “Universal design for learning (UDL) is a framework to improve and optimize teaching and learning for all people based on scientific insights into how humans learn” (CAST, 2023, para. 1). While UDL can support students with disabilities, it is designed to help improve learning for all students, including those in higher education (Li et al., 2024). The UDL principles, guidelines, and checkpoints are available in Figure 1.

Figure 1

CAST (2018). Universal design for learning guidelines version 2.2 [graphic organizer]. Wakefield, MA. Retrieved from http://udlguidelines.cast.org

Positive results of UDL implementation include increasing engagement and access, addressing learner variability, positive student perceptions, improving the learning process, and decreasing learning barriers (Al Azawei et al., 2016; Brandt & Szarkowski, 2022; Capp, 2017; Crevecoeur et al., 2014; Cumming & Rose, 2021; Ewe & Galvin, 2023; Fornauf & Erickson, 2020; Ok et al., 2016; Rao et al., 2014; Seok et al., 2018; Yang et al., 2024). Student responses to UDL implementation have generally been positive (Black et al., 2015; Smith, 2012). A recent meta-analysis found that student achievement was greater in UDL-based courses rather than non-UDL courses (King-Sears et al., 2023). An example of implementing UDL included the use of multiple means of representation of unit materials like lectures, downloadable audio recordings, and lecture transcripts; multiple means of engagement with 24/7 access to course materials and self-paced summative topic quizzes; and multiple means of expression through hurdle quizzes that let students check their understanding throughout the course and choice of topic for written tasks led attrition to decrease from nearly 16% to just over 7% and supported increased student engagement (Garrad & Nolan, 2023). These benefits of implementing UDL do not come without some challenges for faculty and IDs.

A challenge for IDs and other training faculty in the UDL framework is that UDL is loosely defined from an operational sense making it difficult to implement and measure effectiveness (Diedrich, 2021), especially when UDL is referred to as an intervention, practice, or framework (Basham & Blackorby, 2021). With 31 checkpoints, it is unlikely that the entirety of the UDL framework can be applied in one course, much less one unit or class session. This is a challenge for training faculty in UDL, but also affects faculty since applying the UDL framework varies as each faculty member can choose to adopt it differently (Basham & Blackorby, 2021; Ok et al., 2016; Rao & Cook, 2021). Other faculty challenges included those related specifically to implementing UDL: a lack of time, institutional support, resources, and knowledge of UDL (Hills et al., 2022). Since there is a knowledge barrier to UDL implementation, there is a need for UDL training or professional development (Oyarzun et al., 2021; Westine et al., 2019). This training can be provided by IDs. Frequently, IDs work in course improvement and development, collaborating with and supporting faculty, staff, and students (Drysdale, 2021; Magruder et al., 2019; Ritzhaupt & Kumar, 2015). The relationship between faculty and IDs is an essential aspect of instructional design in higher education (Magruder et al., 2019). Similarly, it is important to consider both faculty and IDs perspectives in this research to fully explore the lived experience of implementing UDL in higher education.

IDs provide professional learning opportunities for faculty to support planning, implementation, and evaluation of courses (Xie et al., 2021). Some IDs ensure accessibility compliance. In offering support to faculty, IDs can help enhance student motivation and engagement, suggesting inclusive pedagogical practices (like UDL or culturally responsive pedagogy), and modeling technology integration. The COVID-19 pandemic opened further avenues for IDs to support higher education faculty, including the need for more multimodal courses, which aligns to UDL principles (Xie et al., 2021). UDL is one of the best practices or teaching theories that IDs can help faculty apply (Magruder et al., 2019).

IDs working in higher education play an important role in UDL implementation and have extensive experience working with faculty in designing instructional materials and selecting content and teaching strategies. Their experiences can provide valuable insight into the practical challenges and opportunities associated with UDL implementation in higher education and in supporting faculty with course design. UDL can be a valuable framework for IDs, such as addressing social justice and inclusion issues when designing courses (Rogers-Shaw, 2018). This includes ensuring that instructors comprehend the details involved with access (Moore, 2020). IDs need to ask faculty questions and give concrete examples of UDL implementation to help faculty create learning environments conducive to students meeting course objectives. There is a need for ongoing learning, implementation, and deliberation when applying the UDL framework in higher education. UDL can be recommended by IDs for more intentional course design using inclusive teaching strategies (Moore, 2020).

IDs were surveyed and participated in a focus group about UDL and active learning (Rogers & Gronseth, 2021). IDs felt that accessibility was an important part of UDL and defined UDL as designing to the margins with courses that are accessible and culturally responsive. In other words, UDL checkpoints and techniques help faculty design courses that are accessible to students with a variety of learning needs and culturally responsive. Respondents applied UDL by centering students in the learning process and providing multiple formats of content and discussed the importance of offering UDL training for faculty (Rogers & Gronseth, 2021).

Singleton and colleagues (2019) interviewed IDs, along with analyzing documents analysis regarding UDL implementation in the online course development process. IDs feared overwhelming new faculty, and there were inconsistencies in how IDs approached UDL implementation. Barriers to adopting UDL included a lack of administrative mandates or enforcement, and not being part of promotion and tenure. Adjunct faculty often do not receive compensation or ID support in designing courses, making it challenging to implement UDL (Singleton et al., 2019). Singleton et al. (2019) recommends several ways to improve UDL adoption by faculty: delivering a consistent approach to UDL implementation, recommending prescriptive UDL strategies for online courses, and focusing on specific UDL techniques. It was also recommended to appeal to faculty through the ID and faculty relationship to do the right thing for student success by implementing UDL. Focusing on a few strategies, such as splitting up longer videos into shorter videos or adding knowledge check questions and focusing on inclusive design choices can result in faculty UDL implementation (Singleton et al., 2019).

The research design for this study was qualitative hermeneutic phenomenology (Vagle, 2018). Semi-structured interviews were used with faculty and IDs participants to explore the experience and meaning of implementing UDL in higher education. Since hermeneutic phenomenology is a highly interpretive type of research, it is important to be explicit about researcher positionality. Breanne Kirsch began her UDL journey while completing her master’s degree in education specializing in educational technology. During her last couple of semesters, she learned about the UDL framework. The idealism of UDL diminishing learning barriers and meeting the learning needs of all students drew the researcher’s attention. After this, she explored UDL in her own work as a librarian. Breanne began implementing UDL techniques in her library instruction sessions as well as the one-credit library courses she teaches. She received positive student feedback and used UDL recommendations to create multimodal training materials for student workers in the library.

After the successes of implementing UDL in the library over time, Breanne Kirsch began speaking to other faculty about the potential of UDL in higher education. She led a UDL faculty learning community and read Reach Everyone, Teach Everyone by Tobin and Behling. Additionally, the Breanne helped develop the new general education curriculum requirements to include UDL. Since many faculty had not previously heard about UDL, the researcher began to offer a UDL academy in the summer of 2021 (Kirsch, 2023; Kirsch, 2024). With this perspective, the researcher is biased towards seeing the benefits of UDL implementation. Breanne Kirsch was aware of her own potential bias as she conducted the study and explored her assumptions and biases in a researcher journal as the study progressed to consciously question her own perspectives and how they may have influenced her interpretation of the data.

Tian Luo is a tenured associate professor who chaired Breanne’s dissertation research, which forms the basis of the present study. Her scholarship primarily focuses on teaching and learning through digital technologies, with a strong emphasis on promoting diversity and inclusion. She has published extensively on topics related to UDL.

Purposive sampling was used to recruit five faculty and five ID participants that implemented UDL or assisted faculty in implementing UDL in higher education and had participated in a pilot study and survey (Kirsch & Luo, 2023). Ten participants from varied disciplines, types of institutions, and experience with UDL were selected from a group of 15 faculty and IDs that expressed interest in participating in the study. Participants included nine Caucasians, and one Asian made up of eight women and two men aged 30-59. Table 1 lists the role, experience, and institution for each participant. Pseudonyms are used for participants.

Table 1

Participant role, experience, and institutional information

Pseudonym | Role | UDL Familiarity | Courses/ Projects | Institution |

Brandy | Faculty- Previously Psychology, now Research and Evaluation | 3-4 years | 2 or 3 | Private- Technical University- urban, Northeast- 10,001-20,000 students |

Charlie | Faculty- Librarian | 3-4 years | 2 or 3 | Public- University- rural Southeast- 5,001-10,000 students |

Elizabeth | Faculty- English | 5+ years | 5+ | Public- Technical College- urban Southeast- 5,001-10,000 students |

Madeline | Faculty- Sociology | 3-4 years | 4 or 5 | Private- University- urban Midwest- under 1000 students |

Suzie | Faculty- Nursing | 5+ years | 5+ | Public- Medical University- urban Midwest- 1001-5000 students |

Adrian | ID or EdTech | 5+ years | 5+ | Private- College- suburban Midwest- under 1000 students |

Echo | ID or EdTech | 3-4 years | 5+ | Private- University- rural West- 40,001-50,000 students |

Hannah | ID or EdTech | 3-4 years | 5+ | Public- Community College- urban West- over 50,000 students |

Michelle | ID or EdTech | 3-4 years | 5+ | Public- University- urban Midwest- 10,001-20,000 students |

Snoopy | ID or EdTech | 5+ years | 2 or 3 | Private- College- suburban Southeast- 1,001-5,000 students |

Note: The line in the middle of the tables divide the faculty and ID participants.

Initial semi-structured interview questions were used during the first interview, along with probing questions to ask for more detail or explanation of participants’ responses. To help develop rapport with participants, the researcher asked several opening questions before going into the questions for the study. Interview protocol is available in the appendix. The researcher journal and transcript from the first interview were used to develop questions for the second interview to elaborate on statements made by the participants. A pilot test of the interview instruments was conducted to improve the clarity of the interview questions with an educator who met the eligibility criteria for the study and was familiar with UDL.

This IRB approved study was held virtually in Zoom with two semi-structured interviews. Interviews were audio recorded to create automatic transcripts, which were edited for accuracy. The second interview took place approximately one week after the first interview to allow time for the researcher to initially review and analyze the first interview to create questions for the second interview. The interviews took between 30 and 60 minutes to complete.

Three types of comparisons were made regarding the lived experiences of faculty and IDs in implementing UDL in postsecondary education: individual lived experiences of faculty members, individual lived experiences of IDs, and lived experiences shared between faculty and IDs. Analysis of the first and final semi-structured interviews occurred with a whole-parts-whole process recommended by Vagle (2018), similar to the hermeneutic circle (Heidegger, 1962). First, the researcher conducted a holistic reading of the entire transcript, followed by a line-by-line reading with notetaking and marking of excerpts, noting potential follow-up questions for the second interview, and subsequent readings to code and articulate meanings and themes (Vagle, 2018). The researcher journal was used to help ensure reliability by bridling researcher pre-understandings so participant perspectives and experiences could be reviewed with a more open mind. Reflexivity was used throughout the research process by responding to the following questions, similar to those posed by Dibley et al. (2022) to realize how past experience and pre-understandings inform, but do not rule research findings.

What about my own past experiences helps or hinders this research and what should I do about it?

What do I hear in this participant’s story and how does this challenge my pre-understanding of UDL implementation?

Am I open to other perspectives and avoid introducing bias by asking ‘can you explain’ rather than ‘is that because’?

Am I open to alternative explanations and meanings within the data or am I only seeing what I want or expect to see?

Engaging in these questions within the researcher journal helped to open the researcher up to other explanations, perspectives, and experiences of the participants. Additionally, the researcher spent two interview sessions with each participant for prolonged engagement and gained a better understanding of their context and perspective (Peoples, 2021). In conjunction with the hermeneutic circle, data for each transcript were coded first, phenomenologically, and then pattern coding was applied per Saldaña’s (2021) recommendations. In this case, it involved what the lived experience of UDL implementation in higher education is and what meanings are ascribed to UDL by participants with the experience of implementing UDL in higher education.

Faculty and IDs perceived the implementation of UDL to be worthwhile but with challenges and a need to tie implementation firmly to outcomes.

The lived experiences of participants when implementing UDL in higher education was illustrated with five primary themes (See Table 2). Participants spoke about the lived experience of practical UDL implementation, involving the three overarching UDL principles of providing multiple means of action and expression, representation, and engagement, as well as communicating expectations and using open educational resources (OER). Emotional resonance was described by all but one faculty and one ID with their affective responses and mindset during their lived experience of implementing UDL in higher education. In evaluating the impact of a UDL implementation, participants shared outcomes or results from practical advantages like minimizing barriers, advancing accessibility, or improving course quality to student related responses in attitudes, autonomy, and their experience. All but two faculty members discussed professional empowerment they either received or supported others when implementing UDL in higher education. All but one ID described navigating constraints they or others encountered when implementing UDL.

Table 2

Participants’ lived experiences implementing UDL in higher education

Pseudonym | Practical UDL Implementation | Emotional Resonance with UDL | Evaluating Impact | Professional Empowerment | Navigating Constraints |

Brandy | X | X | X | X | X |

Charlie | X | X | X | X | |

Elizabeth | X | X | X | X | X |

Madeline | X | X | X | X | |

Suzie | X | X | X | X | |

Adrian | X | X | X | X | X |

Echo | X | X | X | ||

Hannah | X | X | X | X | X |

Michelle | X | X | X | X | X |

Snoopy | X | X | X | X | X |

Mentions | 244 | 151 | 146 | 100 | 34 |

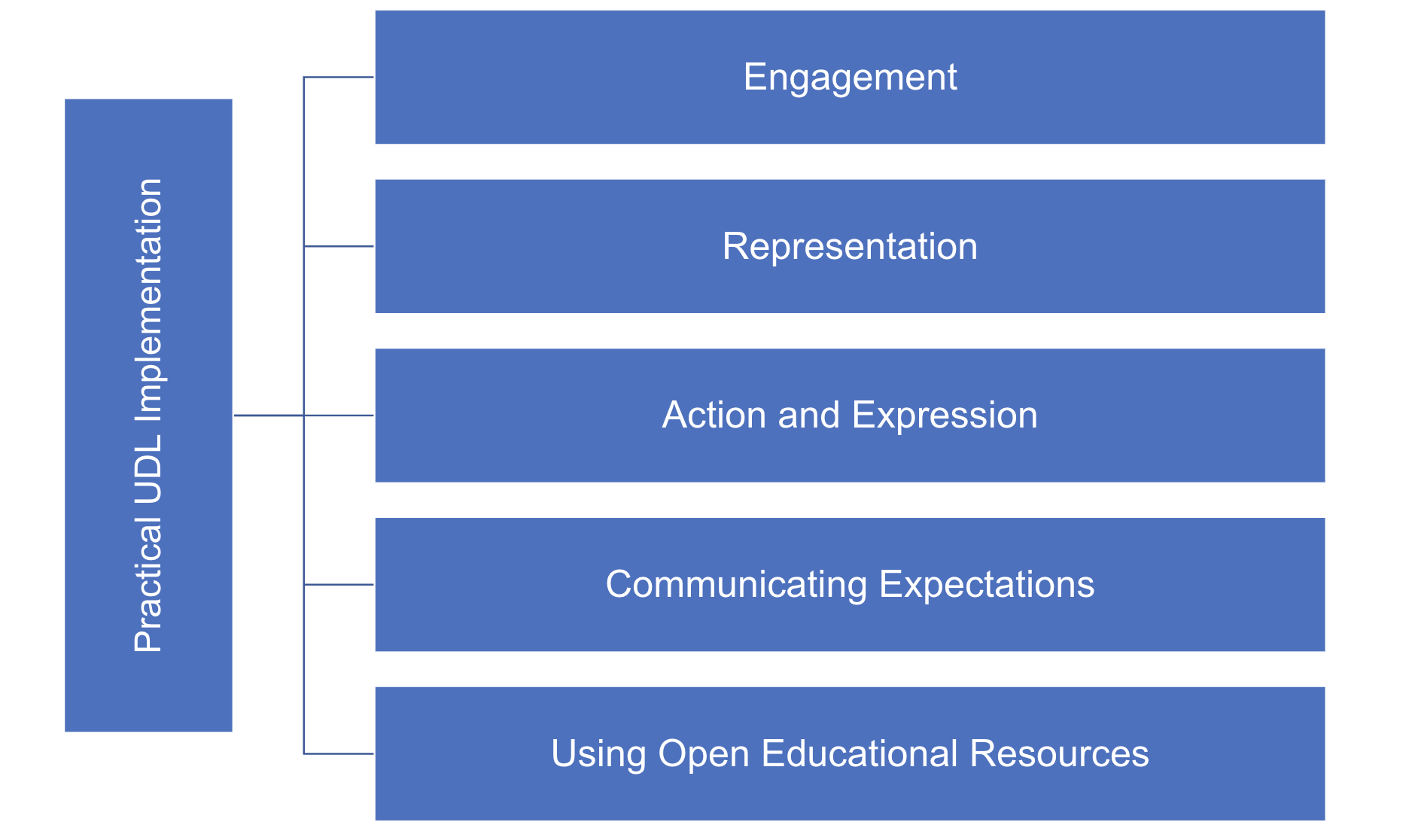

Figure 2

Subthemes for the Lived Experience of Practical UDL Implementation Theme

The theme of practical UDL implementation had five sub-themes, as shown in Figure 2. All faculty implemented action and expression by offering variety in their assignments or supporting students in setting goals and project management under executive function. Suzie focused on action and expression by “giving options to the students when possible within the assignments” and “with students working with different tools for completion of coursework.” Representation was discussed by most participants in terms of accessibility efforts of captioning, alternative text, and transcripts. Suzie felt that “representation is the easiest to do, that you see immediate results.” Engagement was addressed by all participants with self-regulation, guidance, and utilizing different approaches to help students comprehend concepts. Snoopy shared how he encouraged student self-regulation by “setting up a calendar on your phone using alarms.” Michelle felt that providing choice mattered for her students and “when people feel like they’re in control of their learning, they tend to engage.” Three participants described how they communicated expectations with students verbally, through emails, and within rubrics. Hannah shared expectations during her instructor introduction and noted that “UDL doesn’t ask us to change our expectations.” Three participants reimagined UDL and described how they felt OER fit into the framework. Adrian was excited about open educational pedagogy (OEP) since he felt “OEP is the natural evolution of taking the ideas behind OER and then broadening them into the UDL space.” While the specific UDL techniques implemented by faculty and IDs varied, they all utilized components of the principles of the UDL framework. Most participants felt an emotional resonance with UDL and discussed six subthemes, as shown in Figure 3.

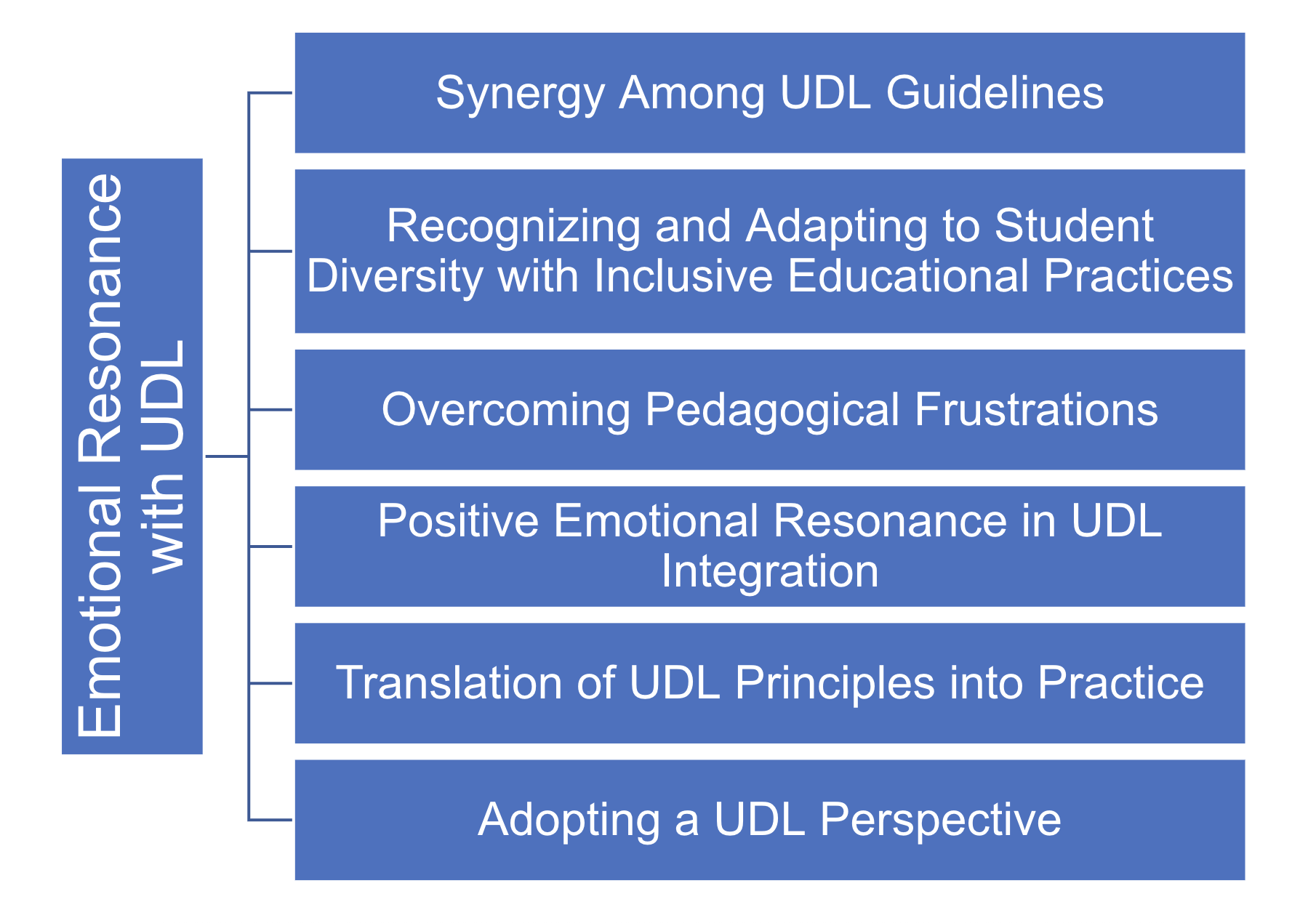

Figure 3

Subthemes for the emotional resonance with UDL theme

Eight participants shared how UDL and other inclusive and effective pedagogies overlap in diversity, equity, and inclusion goals. Hannah was interested in the rising to equity initiative planned by CAST and believed that UDL comes from “a lens of neurodiversity as the norm.” She stated that “inclusive pedagogy I think are aligned with UDL.” Michelle said, “I don’t feel like I can design in a different way anymore. I’m getting to the point where it would feel wrong not to offer choice.” Hannah felt there was synergy among the UDL guidelines when stating that “a single strategy can support multiple guidelines,” such as gamification fitting with comprehension, self-regulation, and mastery-oriented feedback during a debriefing session. Different people translate UDL into practice in contrasting ways and participants adopted a UDL perspective.

Several affective responses explore the contrasting ways that participants navigated the complexity of the UDL framework. Hannah stated that “there are so many varieties that we’ve been exposed to and how there are different ways that people practically interpret the limited information available in the framework… There’s not really a definitive interpretation, but people want one.” Madeline mentioned feeling guilty that she did not have enough time to utilize the same UDL techniques in all of her classes. Michelle talked about seeing faculty feeling overwhelmed and overworked during faculty learning communities. Brandy felt committed to including the principles of UDL in her course design. All participants shared another aspect of the lived experience of implementing UDL: evaluating impact, as seen in Figure 4.

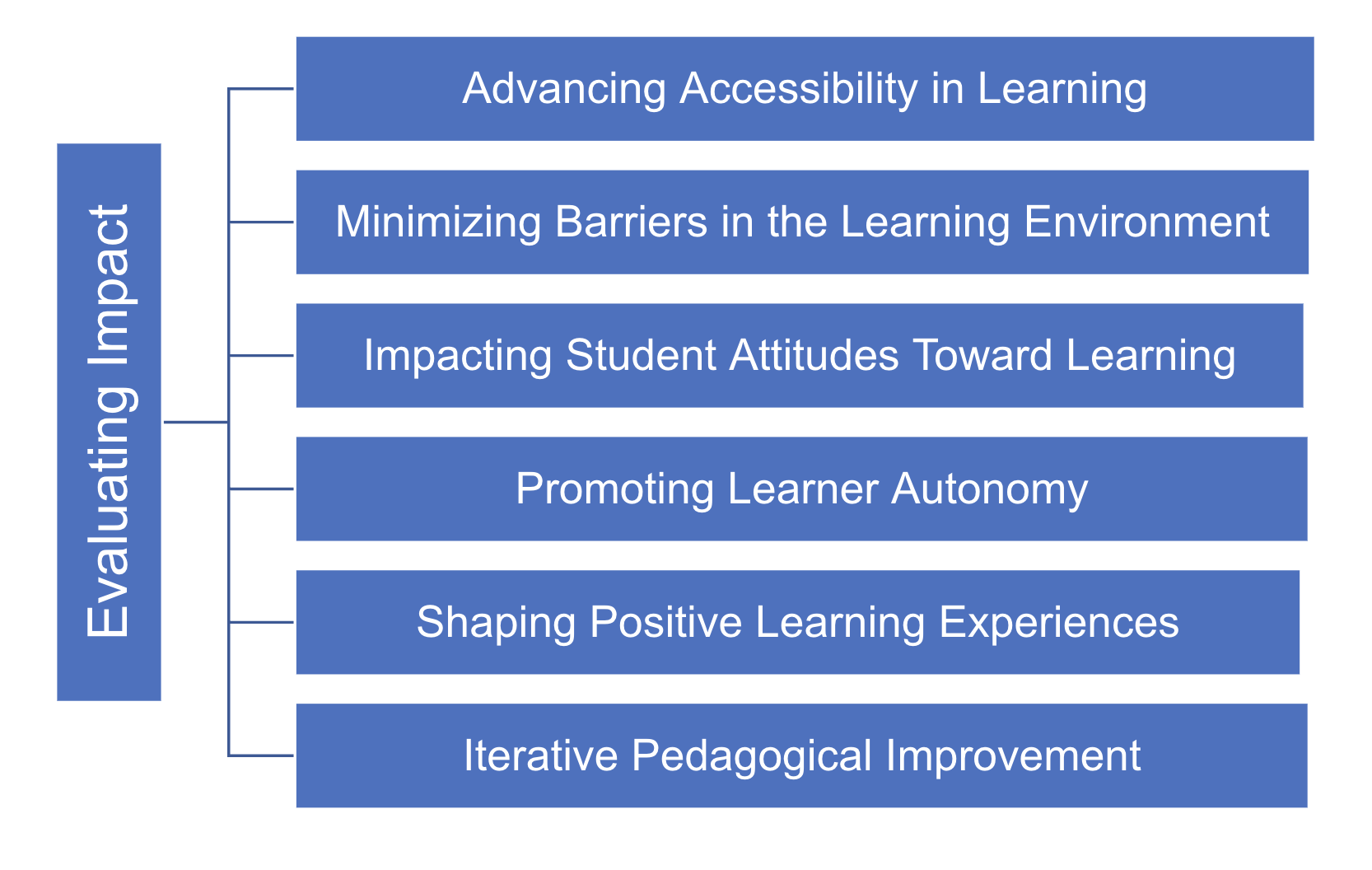

Figure 4

Subthemes for the evaluating impact theme

Participants spoke of evaluating impact through advancing accessibility in learning, minimizing barriers in the learning environment, impacting student attitudes toward learning, promoting learner autonomy, shaping positive learning experiences, and iterative pedagogical improvement. Advancing accessibility in learning was expressed as one of the first impacts participants experienced. Michelle stated, “UDL really helps with bringing greater equity to learning.” Snoopy believed that “UDL involves trying to eliminate barriers…With UDL, we're looking to discover a barrier and then discover a way around, under, or over so that the barriers can be removed.” Other impacts related to students’ attitudes, autonomy, and the learning experience. Suzie reported receiving positive comments from students about her UDL approaches and Elizabeth found that UDL positively changed students’ attitude about writing. Brandy, Michelle, and Hannah mentioned that UDL gives students autonomy over their learning. Elizabeth believed that “UDL is the teacher and the students working together to improve the learning experience.” Using UDL helped faculty evolve their teaching to be more effective teachers. Elizabeth stated, “UDL is the evolution of your teaching, and it does not remain static, but it changes.” Two additional themes related to the lived experience of implementing UDL in postsecondary education were professional empowerment (Figure 5) and navigating constraints (Figure 6).

Figure 5

Subthemes for the professional empowerment theme

Professional empowerment was a theme emphasized more by IDs, though three faculty also discussed this theme. Professional empowerment relates to accessible teaching development, gaining faculty buy-in, readiness and openness to pedagogical shifts, and demonstrating UDL in action. Adrian came to UDL from accessibility and then broadened his understanding of UDL. Three participants spoke of how vital modeling UDL is as part of training and supporting faculty. Adrian modeled UDL as he taught faculty about UDL during a weeklong new faculty orientation. Snoopy also modeled UDL during every consultation he had with faculty and in workshops. Gaining faculty buy-in was exemplified by Michelle and needing to “reach a sufficient number of faculty who do this, make it as visible as possible for their colleagues to see that this is effective.” This relates to readiness and openness to pedagogical shifts. Adrian mentioned that faculty were receptive to UDL and that newer faculty were more receptive to UDL than faculty that had been teaching awhile. It is important to consider faculty receptiveness and how faculty can be convinced to implement UDL.

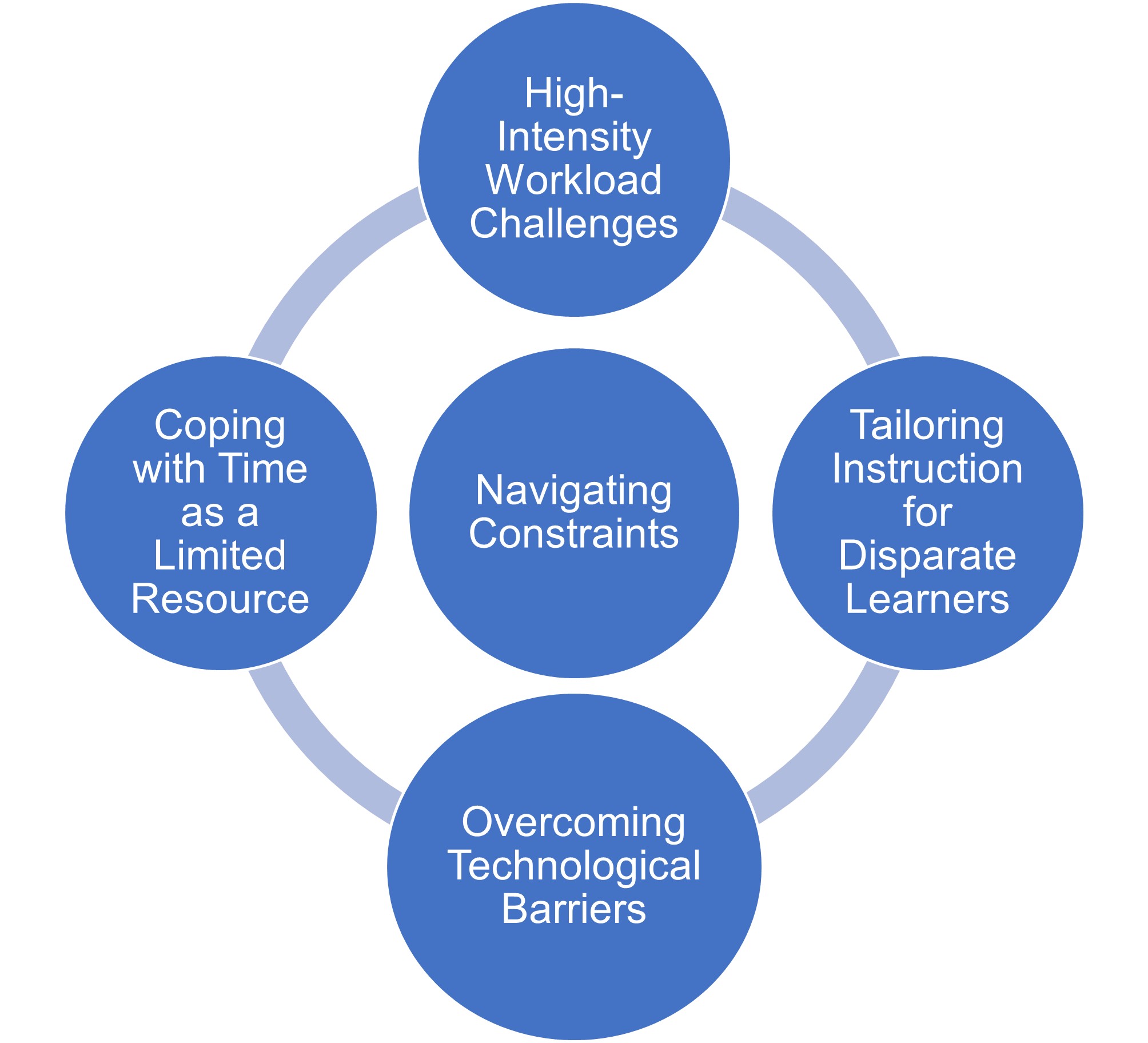

Figure 6

Subthemes for the navigating constraints theme

Navigating constraints included high-intensity workload challenges, tailoring instruction for disparate learners, overcoming technological barriers, coping with time as a limited resource, overcoming bias, and gaining support from administrators. Hannah described the challenge of overcoming her own bias towards text materials and using UDL “at every decision point trying to get outside of my own head, my own biases and trying to think from the perspective of other people.” Adrian, Elizabeth, Madeline, and Charlie felt that implementing UDL is more work on the front end before the class begins. Charlie expanded on this stating, “but when you actually have it all built and ready before the semester and you begin the class, it's easier for the teacher; it's easier for the students.” Madeline discussed the lack of time to implement UDL in all her courses at once. Brandy mentioned that UDL “makes you think everybody is going to enjoy the changes you’ve made to a course and that’s not guaranteed.” Navigating these constraints could be diminished by providing relevant examples of UDL for faculty to make utilizing UDL practices easier. Additional suggestions from participants included a UDL checklist, training, administrative support, and the need for additional research on UDL effectiveness. Participants’ lived experience has led to the meanings they ascribed to UDL.

Faculty and ID participants shared what implementing UDL in higher education meant for them (see Table 3). Participants recognized UDL’s ability to create inclusive practices for equitable learning and the connectedness between UDL and pedagogical approaches or theories. They used UDL as a blueprint for effective teaching and found meaning in UDL’s capability for creating accessible learning landscapes. They also explained the process of implementing UDL using metaphorical insights.

Table 3

Participants assigning meaning to UDL

Pseudonym | Inclusive Practices for Equitable Learning | Connectedness Between UDL and Pedagogical Approaches and Theories | Blueprint for Effective Teaching | Accessible Learning Landscapes | Metaphorical Insights for the Process |

Brandy | X | X | X | X | |

Charlie | X | X | X | ||

Elizabeth | X | X | X | ||

Madeline | X | X | X | ||

Suzie | X | X | X | X | |

Adrian | X | X | X | ||

Echo | |||||

Hannah | X | X | X | ||

Michelle | X | X | X | X | X |

Snoopy | X | ||||

Mentions | 14 | 8 | 8 | 6 | 3 |

The meaning ascribed most frequently was inclusive practices for equitable learning. Brandy stated that she did not know the difference between UDL, and inclusive or equitable teaching and equity minded teaching. She felt the goal of each of these is similar to make courses “accessible to all learners regardless of differences that they may have in a variety of ways, whether it be disability, race or ethnicity, gender preparedness for college.” Adrian felt that “understanding UDL is placed in decreasing barriers and promoting equity.” Madeline stated, “UDL just means trying to do my best to make the class appropriate for every single individual that's in it.” Michelle discussed how “UDL really helps with bringing greater equity to learning.” The meaning of building equity closely relates to the lived experience of recognizing and adapting to student diversity with inclusive educational practices, advancing accessibility in learning, and minimizing learning barriers.

Participants found a meaningful connectedness between UDL and other pedagogical approaches and theories. Four faculty and one ID recognized this meaning along with the zone of proximal development, Quality Matters, critical disability theory, cognitivism, experiential learning, and backwards design. Elizabeth believed, “UDL fits in with my personal and professional theories about how students learn. So, it gives me structure to implement those theories.” Michelle described how UDL fits with critical disability theory, “What UDL is essentially saying is if we can create a space that works for every different way that people's brains and bodies work and engage in learning, we create a more effective learning experience.” This meaning ascribed to UDL relates to the translation of UDL principles into practice. This interpretation of UDL relates to the meaning of UDL being a blueprint for effective teaching.

When explaining what UDL meant, participants described it as a blueprint, foundation, or structure of their teaching. Five faculty and three ID participants ascribed the meaning of UDL as a blueprint for effective teaching. Suzie discussed UDL as being a framework with a set of clearly laid out principles, “It [UDL] does not specify what form you have to use. This framework, it gives us more direction and what we can do before the semester begins.” Several participants ascribe UDL as being a foundation. Brandy said, “At the end of the day, the practices that fall under this framework are really just good teaching… That's just sort of the foundation for good teaching.” Michelle stated, “This was something that very foundationally informed my approach to instructional design.” This meaning can help inform how UDL is implemented and during the process of UDL implementation, whether UDL is viewed as the foundation of teaching or a practical framework to be applied. Similarly, the theme of accessible learning landscapes can also inform how UDL is implemented in higher education.

Accessibility is part of what makes a course equitable. This narrower meaning attributed to UDL was described by two faculty and four ID participants. Brandy felt that UDL is “an opportunity to design your course to make it accessible to students from different backgrounds, different ways of thinking.” Michelle initially believed that UDL was making sure that everything is accessible, “I think a lot of people start there, believing that accessibility is the equivalent of UDL.” She expanded her understanding of UDL as she grew professionally.

Participants used metaphorical insights for the process of UDL to construct meaning or internalize what UDL represents. Two faculty participants and one ID discussed metaphors for their UDL implementation process with three mentions as a patchwork quilt, a Jenga tower, or a journey. Madeline stated, “It's kind of like a patchwork quilt, where I try to keep doing a little bit along the way to keep making them better … It just has to be something that's an ongoing process.” Elizabeth described the process as a Jenga tower with the blocks being what faculty are already doing and the holes being the parts that need to still be addressed. Michelle stated, “There is not an endpoint that you must achieve. This is a journey of slow implementation… Thinking of it as a practice rather than an accomplishment.” These metaphorical insights can help faculty and IDs interpret UDL implementation as an ongoing process over time, like iterative pedagogical improvement or the evolving synthesis of UDL pedagogical change in postsecondary education.

Participants explained six steps in the UDL implementation process: a) starting with UDL discovery, b) preparing and launching the UDL process, c) decision-making in UDL integration, d) implementing UDL strategies, e) evolving synthesis of UDL pedagogical change, and f) embedding UDL practice across the institution (See Table 4).

Table 4

Participants’ themes for the steps in the process of implementing UDL

Pseudonym | UDL Discovery | Preparing and Launching the UDL Process | Decision-Making in UDL Integration | Implementing UDL Strategies | Evolving Synthesis of UDL Pedagogical Change | Embedding UDL Practice Across the Institution |

Brandy | X | X | X | |||

Charlie | X | X | ||||

Elizabeth | X | X | X | |||

Madeline | X | X | X | X | ||

Suzie | X | X | X | X | X | |

Adrian | X | X | X | X | X | |

Echo | X | X | X | |||

Hannah | X | X | X | X | X | X |

Michelle | X | X | X | X | X | |

Snoopy | X | X | X | |||

Mentions | 14 | 20 | 28 | 17 | 38 | 9 |

The first theme or step was UDL discovery for the process of implementing UDL. All participants described their experience of discovering and learning about UDL during their implementation process. Snoopy learned about UDL during his master’s coursework and introduced new faculty to UDL as a way to spread UDL across an institution over time and modelled UDL during consultations and workshops with faculty. Brandy felt training in teaching and UDL should be required for higher education faculty. UDL discovery relates to the theme of professional empowerment experienced by participants.

After UDL discovery, the next step related to preparing and launching the UDL process. Two faculty and three ID participants discussed preparing and launching their UDL implementation process. Participants highlighted techniques which they used during the earliest part of the UDL implementation process. Some examples include Suzie beginning with representation and Echo focusing on heightening the salience of goals and objectives, along with focusing on mastery-oriented feedback. The next step of the implementation process for participants involved decision-making in UDL integration.

One faculty and two ID participants discussed the process of making decisions in their UDL integration. The decision about which guidelines to use necessitated deciding what to prioritize among the 31 guidelines. As a result, participants focused on relevancy, either from their students’ perspective or to their specific course and discipline. For example, Hannah described this theme by “identifying guidelines that are most relevant or applicable to your course and your discipline, makes it very possible for the faculty to make their own determination.” The theme of decision-making in UDL integration is connected to the subtheme of synergy among UDL guidelines. After decision-making, the next step in the process was implementing UDL strategies.

The act of implementing UDL strategies from the practical everyday application to researching UDL and considering contextual elements, involves training, reflection, and application. All participants discussed the process of implementing UDL strategies, which refers to the act of applying the framework rather than practical UDL implementation, related to specific guidelines and checkpoints utilized (one of the themes of the lived experience). Suzie said, “the framework made sense to me in terms of a day-to-day practical application that we can include in the classroom.” Hannah believed that system wide implementation needs champions and to be part of the strategic plan “to infiltrate accountability practice,” similar to the process theme of embedding UDL practice across the institution. Charlie described being proactive during her implementation process, “when you actually have it all built and ready before the semester begins… I'm not worried about making an exception for this one student because I already really put a lot of effort beforehand.” Brandy discussed keeping track of challenges that arose during the semester to address them proactively before teaching the following semester.

After implementing UDL strategies, the next step is the evolving synthesis of UDL pedagogical change and utilizing the plus one strategy over time. Three faculty and four IDs described their UDL implementation process as involving an evolving synthesis of UDL pedagogical change. The plus one approach is one recommended by Tobin and Behling (2018). Madeline puts the plus one approach into practice by applying one UDL technique across all her classes, often in response to a problem she noticed. Suzie mentioned the plus one strategy and implementing UDL as an ongoing process. She said, “it’s hard to implement every principal and strategy in place in one semester.”

After implementing UDL strategies with evolving synthesis of UDL pedagogical change, the last step expressed in the UDL process was embedding UDL practice across the institution. One faculty and three ID participants discussed this theme. Michelle felt that “policy is going to make a difference in what administrators do, what institutions choose to support or not support.” Hannah described how UDL is embedded in the institutional quality standards, but that there is not “willingness in our system yet to associate it with faculty evaluation for that kind of accountability.” She felt that for UDL to be fully implemented across the institution systematically, there should be accountability procedures in place and that UDL should be part of the course blueprint for all courses. Hannah integrated UDL into her institutional quality standards and provided workshops for faculty. Adrian wanted to make UDL an institutional effort with “the idea is that UDL is not an option. It's kind of an expectation that you're going to aim to do.” Echo felt that consistency should be built across all courses from general education to their program with UDL. Embedding UDL practice across the institution is the final step of the process of implementing UDL in higher education.

This hermeneutic phenomenological study aimed to investigate how faculty and IDs interpret and engage with the implementation of UDL in higher education. The lived experience of implementing UDL in higher education was expressed by participants through the constructed themes of professional empowerment, navigating constraints, emotional resonance with UDL, evaluating impact, and practical UDL implementation. Participants discussed the need for UDL training in higher education, which aligns with what is recommended in the literature (Rogers & Gronseth, 2021). IDs spoke of how they trained and supported faculty in implementing UDL with new faculty orientations, trainings, workshops, faculty learning communities, and consultations. This involves faculty readiness and openness to pedagogical shifts and gaining faculty buy-in to attend training and then implement UDL strategies and can relate to the lack of authority of IDs discussed by Drysdale (2021). Demonstrating UDL during faculty consultations or workshops was another technique used by ID participants (Evmenova, 2018). Participants experienced several constraints when implementing UDL, including time (Hills et al., 2022; Linder et al., 2015) and a lack of educational knowledge of administration (Hills et al., 2022; Martin, 2021; Singleton et al., 2019). Participants spoke about challenges of tailoring instruction for disparate learners including student resistance to changes made to the course when applying UDL.

Participants expressed the experience of implementing UDL in higher education through several affective responses. Some felt that one technique, such as gamification, can relate to synergy among UDL guidelines like Ewe and Galvin (2023). Participants believed that UDL relates to inclusive educational practices with accessibility and bringing greater equity to learning, similar to the literature stating the need for UDL in providing inclusive pedagogy (Carlson & Dobson, 2020; Lowenthal et al., 2020; Rogers-Shaw, 2018). The lived experience also involves the practical implementation of specific UDL techniques, such as the guidelines of executive function and self-regulation, which were inherently difficult to implement because they require intrinsic change on the part of the student. Representation appears to be the most straightforward and approachable UDL principle. Implementing UDL advances accessibility, minimizes learning barriers, and involves iterative pedagogical improvement. Promoting accessibility and equity is closely related to perception and representation. Eliminating barriers and learners overcoming obstacles to their learning conforms to what is found the literature (Smith et al., 2019). The positive student attitudes and experience expressed by participants is similar to literature sharing positive student responses to UDL implementation and improving student learning (Black et al., 2015; Kennette & Wilson, 2019; Smith, 2012). Higher student achievement scores are correlated with UDL-implemented courses (King-Sears et al., 2023).

There seems to be a dichotomy in the meaning ascribed to UDL in higher education. On one hand, many people discover the UDL framework from an accessibility standpoint. Others push back against this and see UDL as creating equitable learning or breaking down barriers. More faculty focused on the meaning of UDL connectedness to other pedagogical approaches and theories, while in contrast more instructional designers focused on the meaning in UDL’s capability for creating accessible learning landscapes. UDL is more than accessibility and Lowenthal et al. (2020) agree that compliance with accessibility is not enough. It is also more than offering choice or inclusive design. UDL is a mindset and a complex framework that means multiple things at once to different people. Several participants endorsed the connectedness between UDL and learning theories or pedagogies including culturally responsive pedagogy, which is in agreement with studies (Moore, 2020; Kieran & Anderson, 2019). This study demonstrated the nuances of what meanings are ascribed to UDL by the participants. UDL can be seen as both a practical framework for designing learning environments and a guiding philosophy or movement with an ongoing commitment to inclusion and improving teaching (Howery, 2021; Rao & Cook, 2021).

The process of implementing UDL in higher education involves a series of steps and descriptions shared by participants. Despite a lack of any sharp contrasts in what instructional designers versus faculty focused on when it came to the process of UDL implementation, variations in theme popularity (number of mentions) remained evident and showed that neither faculty nor instructional designers were monolithic in their preferences. First, an individual experiences UDL discovery, usually through professional development. This is similar to the literature highlighting the need for professional development in UDL (Oyarzun et al., 2021; Westine et al., 2019). Preparing and launching the UDL process involves faculty prioritizing where to begin and involves selecting specific guidelines or checkpoints and then applying them in courses. The process is an evolving synthesis of UDL pedagogical change in a course using a plus one approach as Tobin and Behling (2018) recommend rather than an intervention that can be completed after a semester. The literature agrees that implementing UDL is an ongoing process (van Kraayenoord et al., 2014) or a step-by-step approach over time (Evmenova, 2018; Westine et al., 2019).

The UDL implementation process varies for each individual and changes over time, making it challenging to specify which guidelines should be utilized and applied in specific classrooms or at specific institutions. There were notable differences in how faculty and ID participants implemented UDL, for example faculty participants focused more on proactively implementing UDL when updating or designing courses while ID participants focused more on the systematic and deliberate UDL practices characteristic of the process. Recommending specific UDL techniques or checkpoints that should be implemented can stifle or prevent unexpected positive outcomes. This can make it challenging for faculty to implement the framework when they first learn about UDL since they want guidance and specific techniques that they should implement. While IDs can make initial recommendations, it is vital for faculty to critically think about their specific course, context, and student population when choosing guidelines to implement in their courses. In addition to IDs providing faculty training or orientation introducing UDL, there are several other recommended ways to expand UDL across campus. One way is by gaining buy-in throughout the institution, which is also discussed by Moore et al. (2018) and Fovet (2021). Policy is also important for institutional support of UDL, which is also described in the literature (Hitch et al., 2015; Linder, et al., 2015).

All of the ID participants supported faculty in professional development workshops, courses, faculty learning communities, or consultations and introduced UDL to faculty. UDL means different things to different people. Therefore, when IDs discuss UDL with faculty, it would be beneficial to discuss this multitude of meanings. Professional development is crucial to implementing UDL in higher education (Martin, 2021), especially comprehensive training opportunities (Hromalik et al., 2020; Smith Canter et al., 2017; Westine et al., 2019). Providing classroom examples of UDL implementation is an important part of professional development (Oyarzun et al., 2021; Smith Canter et al., 2017). This helps faculty feel less overwhelmed by UDL and also gives faculty a baseline for what UDL can look like, which can inform the conversation about how to implement additional aspects of UDL. Practical implementation of UDL in the classroom is the goal and training should move beyond introducing the framework to helping faculty begin to apply the framework in courses (Hromalik et al., 2020; Westine et al., 2019). Release time and stipends are recommended for professional development to encourage more participation, which could help more faculty participate in training and then implement UDL strategies, which aligns with pre-existing research (Hromalik et al., 2020; Richman et al., 2019; Westine et al., 2019). IDs can use these ideas when designing professional development or holding consultations with faculty where UDL could be a viable framework.

To apply the framework in courses, participants mentioned wanting additional training, a UDL checklist, video refreshers on different guidelines, and supportive technologies for high-flex classrooms. Instructional designers can provide practical advice for implementing UDL in higher education. Additionally, two books that provide practical advice for UDL implementation in higher education include Reach Everyone, Teach Everyone by Tobin and Behling and UDL Navigators in Higher Education: A Field Guide by Black and Moore. Other participants recommended expanding UDL across the institution through administrative support and awareness, policies, and gaining buy-in for UDL as an inclusivity approach. Several participants spoke of the need for more research into UDL effectiveness as a way to make the adoption of UDL practices easier. This relates back to the challenge of viewing UDL as an intervention (Diedrich, 2021) rather than a framework with an ongoing implementation process. There are some studies on UDL effectiveness (Capp, 2017; Espada-Chavarria et al., 2023; Ok et al., 2016; Seok et al., 2018), but they are not widespread and the ways UDL is implemented by different individuals vary greatly, making it impossible to broadly generalize UDL effectiveness as a framework.

The different methods of applying the framework make it unrealistic to create a UDL checklist or templates that share all of the possibilities for applying different aspects of UDL, though a checklist could be used as a starting point for novice faculty and IDs, adapted from the list of checkpoints and examples available from CAST (2011). A syllabus template incorporating UDL techniques could be shared with faculty. While a course template would be more time intensive to create, it could help make UDL adoption more widespread with examples of UDL content and assessments. Faculty can participate in a variety of professional development opportunities, training, or consultations with IDs to learn about the UDL framework and to begin implementing UDL in higher education. Faculty are encouraged to consider ways that UDL guidelines and checkpoints can be implemented in their classroom to diminish learning barriers and lead to accessible, inclusive, and equitable learning opportunities for students. Faculty and administrators should consider creating educational policies that highlight the importance of using UDL to foster a culture of inclusivity.

There are several limitations to this study. The multiple understandings of UDL are a limitation since there is not one meaning or one way of implementing UDL experienced by all participants. This made interpreting the findings more holistically across all participants challenging. In hermeneutic phenomenology, the researcher interprets the data, which can introduce bias or misinterpreting participants’ experiences. This was mitigated in part with the reflexive, hermeneutic circle of reviewing the transcripts several times to ensure the alignment of interpretations with participants’ statements. There is little racial diversity since all participants were the same race but one, which limits considerations about the potential interplay of race in the lived experience of UDL implementation in higher education. While participants were from a variety of types of institutions in different states with different levels of experience, there were no participants with only one or two years of experience with implementing UDL, so the novice perspective is not represented in this study.

To address these limitations and build on the findings of this study, future research should consider employing mixed-methods approaches that combine qualitative and quantitative data. For example, qualitative interviews could be paired with focus groups or surveys to capture broader patterns and more diverse perspectives on UDL implementation. Additionally, increasing the sample size and prioritizing recruitment strategies that enhance racial, institutional, and experiential diversity would strengthen the findings. Longitudinal studies could also provide insights into how UDL implementation evolves over time, particularly for novice faculty and instructional designers. Finally, incorporating the perspectives of students through focus groups, surveys, or case studies would offer a more comprehensive understanding of how UDL impacts teaching and learning.

Please provide a little background on the college or university where you work (no need to share the name of your institution) and your student population.

Can you share your current position and the types of courses you teach or design or have previously taught or designed?

What does universal design for learning mean to you?

In this study, we will define UDL as a framework. We will focus on the practical perspective of implementing specific UDL guidelines and checkpoints within the framework.

Can you tell me about how you first learned about UDL?

When was the last time you implemented UDL in a course?

Tell me the story of a time that you implemented UDL in higher education. What was your experience like? Please share all of the details that you can remember.

What does the implementation of UDL in higher education mean to you?

Why did you choose to implement UDL?

What worked well when you implemented UDL?

Are there particular UDL guidelines that you focus on implementing in your courses?

Why did you focus on those guidelines?

What challenges did you experience in implementing UDL?

What benefits did you experience or witness with your students after implementing those guidelines?

How did you feel about implementing UDL?

How would you evaluate this UDL implementation?

Please provide a little background on the college or university where you work (no need to share the name of your institution) and your student population.

Can you share your current position and main duties at your institution?

What does universal design for learning mean to you?

In this study, we will define UDL as a framework. We will focus on the practical perspective of implementing specific UDL guidelines and checkpoints within the framework.

Can you tell me about how you first learned about UDL?

How have you used UDL in your work, either yourself or when supporting faculty?

When was the last time you used UDL guidelines or checkpoints?

Tell me the story of a time that you implemented UDL in higher education, either yourself or supporting faculty in integrating UDL guidelines in their courses. What was your experience like? Please share all of the details that you can remember.

What does the implementation of UDL in higher education mean to you?

Why did you choose to use UDL?

What worked well when you have applied UDL?

Are there particular UDL guidelines that you most frequently use?

Why did you focus on those guidelines?

What challenges did you experience in applying UDL?

What benefits did you experience or witness after using those guidelines?

How did you feel about implementing UDL?

How would you evaluate this UDL implementation?

Can you provide more details about how you learned about UDL?

Can you clarify what you meant when you described your UDL implementation?

Can you expand on what UDL means to you?

Do you have anything else you would like to share about your experience implementing UDL in higher education?